On a May afternoon two years ago, Christyn Akin-Crockett found herself in an unusual situation. Standing in an alley north of downtown Columbus, Ohio, the church administrator was dressed in black and staring at a run-down single-family home.

Akin-Crockett, 42, had heard that a woman in the area — identified to her only as “Becka” — was responsible for multiple killings, including her father’s.

In an interview, Akin-Crockett said she had previously tried to get local authorities to investigate Wayne Akin’s death as suspicious. When she’d gone to her father’s apartment after his body was found on April 17, 2023, she said she found women’s shorts and underwear on the floor, and his phone and wallet were missing. But when she went to Columbus police with her concerns, she said, an officer told her investigators had to wait for the results of toxicology testing to determine if Akin’s death was suspicious.

Frustrated, Akin-Crockett said she took matters into her own hands after someone reached out to her family via Facebook with information about his death and who may have been responsible for it. The tip prompted what Akin-Crockett described as a vigilante mission that she said brought her face to face with the woman authorities later identified as Rebecca Auborn, a sex worker and alleged serial killer charged in October 2023 with targeting at least four customers, including Akin, with fatal doses of fentanyl.

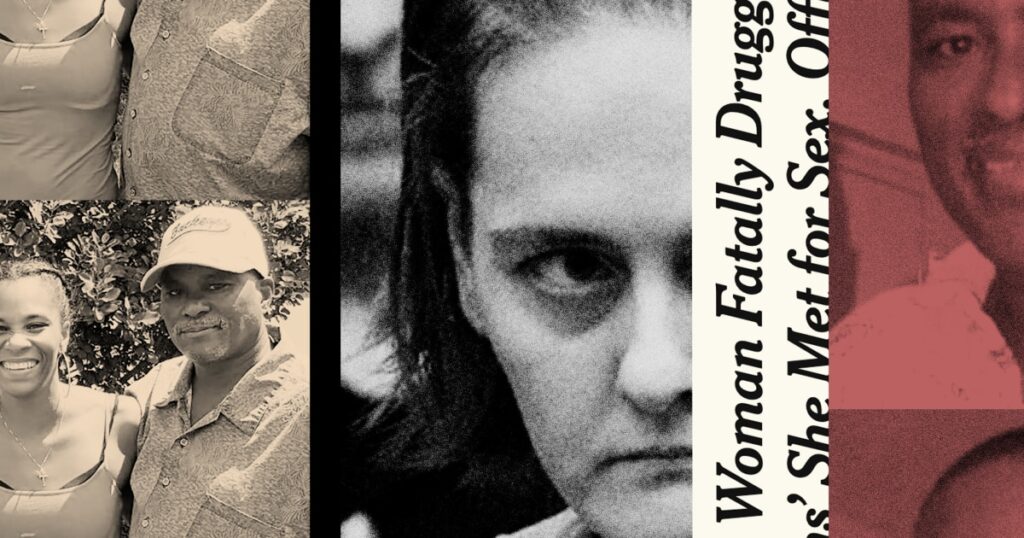

Prosecutors have accused Auborn, 34, of killing the men between January and June of that year. She was charged with trying to kill a fifth person in December 2022, an indictment shows.

Auborn has pleaded not guilty and was found competent to stand trial earlier this month. Her lawyer has not responded to requests for comment.

Akin-Crockett said she eventually provided the information — which came in a series of text messages from a woman who said she’d known Akin — to a Columbus police detective who investigated her father’s death. But that was months later, Akin-Crockett said, after the June 17, 2023, death of a fourth person whom prosecutors charged Auborn with killing.

Akin-Crockett had two goals with her trip to the alley that day: She wanted her father’s belongings back and she wanted his killer behind bars.

“My intention,” Akin-Crockett said, was “to tackle her and restrain her until the cops got there.”

A spokesperson for the Columbus Division of Police did not respond to a detailed list of questions about Akin-Crockett’s account but said the department is looking into the matter.

A series of illuminating texts

The messages that led Akin-Crockett to the alley began May 6, 2023, a few weeks after Akin’s death. Akin-Crockett declined to identify the woman who sent the messages to protect her privacy, but she provided screenshots of the texts to NBC News.

Akin-Crockett described her father, a 64-year-old former postal worker who spent years battling drug addiction after a diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome, as a generous family man whom she became estranged from after his descent into illness and addiction. They began to mend their relationship in the years before his death, she said.

The nature of Akin’s relationship with the woman who reached out to Akin-Crockett was unclear, Akin-Crockett said, but they seemed to be friends.

Akin, the woman wrote in one of the messages, “has you come over you get to relax take a shower he feeds you and spends a lot of money so your happy and all he wants is someone to chill with and talk to.”

In another message, the woman asked how Akin died.

“Was it an overdose because I know who did it,” she wrote.

Akin-Crockett texted back that her father’s cause of death wasn’t clear yet — authorities had not completed toxicology testing — but she believed he may have been drugged and left for dead. Akin-Crockett mentioned that his wallet and phone were missing.

“Yeah, her name was becka,” the woman responded. “She’s been doing it” to a few guys. In another text, she added: “Yes she murder him this is the 4 person she has done it to but she’s going to get hers just wait you can only do so many bad things before something is done back to you.”

Akin-Crockett asked her to report the details to the Columbus Division of Police, but the woman declined, saying she had warrants and couldn’t go to jail or testify, according to the messages. But the woman provided Akin-Crockett with the name of an intersection with a camera that might have captured Auborn and Akin together before his death.

In the same text, the woman wrote: “I’m guessing she wasn’t smart enough to take his car, so she would need a ride back meaning she’s going to be on camera at the subway across the street from his house.”

Akin-Crockett asked the woman if she knew Auborn’s last name, according to the messages. She didn’t, she said, but she provided detailed instructions about where Akin-Crockett could find her — an alley near East Weber Road and Atwood Terrace, about a half-mile from Interstate 71.

“When you see any females out just pretend like you are family and you have money for her or something and they will show you right where she is,” the woman wrote.

A couple of hours later, the woman sent another message saying Auborn was at a nearby corner store. She described Auborn’s appearance — short, dirty-blond hair, shorts and a pink hoodie — and said that she had Akin’s phone and was speaking disparagingly of him.

“She didn’t care he was dead,” the woman wrote.

Ready for a confrontation

Akin-Crockett described the location identified by the woman as a fairly rough part of Columbus. Akin-Crockett grew up a mile or two away, she said, and spent her childhood cruising around the area by bike with her siblings.

Because Akin-Crockett was familiar with the neighborhood, she said she didn’t fear a potential confrontation. And besides wearing black stretch pants and a black polo — Akin-Crockett reasoned that a “very aggressive demeanor” might ward off potential trouble — she took no safety precautions when she and her husband parked near the corner store on the afternoon of May 6.

Ittai Crockett said he advised her not to pursue her father’s assailant because it was dangerous and because she would “stick out like a sore thumb,” potentially spooking Auborn and prompting her to flee.

“Christyn, against my wishes, jumped out of the car,” said Ittai Crockett, noting that he is legally blind and remained in their vehicle as his wife began scouring the neighborhood.

By then, neither of the women were at the store, Akin-Crockett said. So she walked to the alley identified by the informant and found what she described as a dingy white house with an old roof.

On the porch, Akin-Crockett saw a woman who appeared to match the informant’s description: she had dirty-blond hair and shorts. But there was no pink hoodie. And she had no way to confirm if the woman was in fact “Becka.”

In a text message, Akin-Crockett had asked the informant for a photo, but she never responded.

Akin-Crockett stared at the house, she said, and the woman with dirty-blond hair remained on the porch for a moment, then went back inside. Moments later, a man emerged, appeared to look at Akin-Crockett, then also went inside.

Akin-Crockett said she watched the house for roughly five minutes — a period that felt like an eternity — and weighed her options.

Because she couldn’t say with absolute certainty that she was looking at the woman described by the informant, she said she didn’t want to potentially hassle the wrong person and “cause chaos for no reason.”

Nor did she call authorities — even though she said she talked with an officer before driving to the neighborhood. The officer told her to dial 911 when she was in the area, Akin-Crockett said.

But given what Akin-Crockett described as lengthy police response times in Columbus and the agency’s prior description of her father’s death as nonsuspicious, she concluded it wasn’t worth calling.

“I wasn’t sure how seriously they’d take it,” she said.

So Akin-Crockett walked back to her car and told Ittai Crockett she thought she saw the woman but couldn’t be certain.

A couple days later, they went to the department’s headquarters to obtain a report related to her father’s death, Akin-Crockett said. While there, she told an officer about the text messages and the camera that might have video of her father with his alleged killer.

“They said, ‘Unfortunately, we would have to wait on toxicology,’” Akin-Crockett recalled the officer saying. “Once that came back, then they could pursue something.”

Charged with murder

It wasn’t until September, three months after the death of a fifth person on June 17, that Akin-Crockett realized the informant had been right — and the woman she’d seen in the alley was the person later charged with killing her father.

The confirmation came from a news report showing Auborn’s mug shot after her indictment in the killing of one of the four men. Her hair looked different, but she had the same sunken cheeks and sickly demeanor, Akin-Crockett said.

In October, Auborn was charged with dozens more crimes, including the robbery and murder of Akin.

Akin-Crockett was grateful that Auborn was finally off the streets, but her frustration has only intensified over what she views as the department’s inaction in the days and weeks following her father’s death.

“They had the power to pursue justice right at that moment, but they did not, and that saddens me,” she said, adding: “When I talk to other people, they’re outraged that we had this information, that we presented this information and it wasn’t taken seriously.”

“Somebody else’s father, brother, loved one should not have had to die,” Ittai Crockett added. “It’s a tragedy.”