In the 1950s, it became clearer than ever that energy was the key to economic growth and higher standards of living. Determined to secure abundant supplies of affordable coal, gas and oil, governments intervened in the free market. Fossil fuel subsidies transformed many lives, including mine.

My parents raised me and my six siblings in a house with one cold water tap and one toilet. Our home in the Dutch town of Hillegom had city gas, produced from coal, which fired a two-pit stove. To access the gas, we had to put a dime in a meter behind our front door. One small coal stove heated our living room—the rest of the house was cold. My chore was to ensure the coal bucket was filled for the night.

Saturday afternoons were bathing day. There was no shower, so my mother would pour hot kettles of water into a small zinc basin on the floor of the kitchen. Two by two we bathed. How my parents bathed I still don’t know. Although we were happy, better economic prospects in Canada, Australia and New Zealand led many Dutch to emigrate, including three of my mother’s siblings.

Huge natural gas reserves were discovered in The Netherlands late in the 1950s. The government subsidized the development of these natural resources to create new economic opportunities, scale up industries and enable families like mine to live in bigger, better homes with luxuries like hot water. The energy companies made astounding profits, yet the subsidies kept growing and never went away—not even after the risks of fossil fuel dependency became undeniable. All around the world, special interests fought to ensure these subsidies would remain and grow.

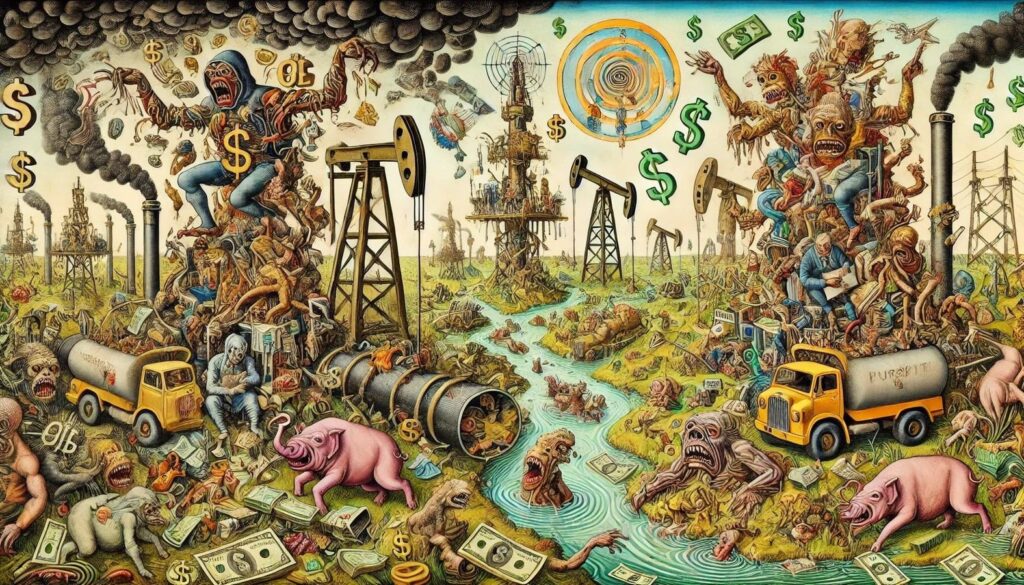

The result was a “swamp.” In the olden days, governments drained swamps to rid them of bloodsucking, malaria-infested mosquitoes. Now, governments have metaphorical swamps, inhabited by special interests and grifters that feed on the status quo at expense of the future. This is a call to recognize and drain two swamps that limit innovation, calcify our politics and undermine the West’s strategic position.

The fossil fuels subsidy swamp contains companies that basically convert taxpayer dollars, one for … [+]

Fossil Swamps

Some years ago, my company, Chrysalix Venture Capital, analyzed the net profits of the 1,801 largest publicly traded oil, gas and coal companies worldwide. As of 2013, they had combined net profits of USD $500 billion and received direct subsidies worth $700 billion. The fossil fuel industry had become dependent on taxpayer funding, so protecting their huge subsidies became a big business attracting vast armies of advisors, consultants and lobbyists. Thousands of them now attend the United Nations’ annual climate conferences.

The subsidies that enabled the development of fossil fuels 75 years ago are peanuts compared to the handouts the industry gets today. The subsidy swamp contains companies that basically convert taxpayer dollars, one for one, into shareholder returns and damaging greenhouse gases.

Even the Paris Agreement, ostensibly a plan to limit climate change to an acceptable level, is swampy. For example, Exxon Mobil CEO Darren Woods advocates for keeping the United States in the Paris Agreement, and why wouldn’t he? His firm has achieved record profits under this regime, and fossil fuel demand continues to grow.

Government Swamps

And then there’s the government swamp. For reasons ranging from regulatory capture to nepotism, bureaucracies have swelled with “bullshit jobs” (an academic term) that offer little return on taxpayers’ money. Once created, jobs in government and special interest organizations tend not to disappear.

Here in Canada, it is not a deep state we have, but rather a shallow state of political maneuverers who vie for lucrative jobs in government and in Canada’s Crown corporations, which consequently underperform. Crown corporations can be very useful, but many are hard to justify in a time of rapidly increasing costs and taxes. Many should cease to exist or at least be privatized and staffed by the best and brightest, too many of whom leave Canada for better opportunities abroad.

You can probably think of additional swamps that formed in the past 75 years, wherever wealth creation became dependent on subsidies, regulation and government support. But what swamps demand and what taxpayers these days can afford are diverging. Many families now spend more on taxes than food, clothing and shelter combined. A good chunk of that tax revenue goes to the swamps, diverting public resources and focus from strategic goals like the energy transition and affordable housing.

How to Drain the Swamps

The status quo has given us economic stagnation, political dysfunction and a worsening climate crisis. If we’re serious about changing these outcomes, we need to drain the swamps. I suggest we begin with two achievable goals:

1. Phase out fossil fuel subsidies gradually. Reduce them by 25% every three to five years to prevent an economic shock. We taxpayers fund subsidies larger than the profits fossil fuel companies make, full stop. We subsidize them to double down on energy technologies from the 60s and 70s while China subsidizes its firms to dominate in cleantech and emerging technologies. It’s like we’re betting taxpayer dollars on 58-year-old Mike Tyson in his recent boxing match against 27-year-old Jake Paul. We can’t win this way.

2. Clean out the bureaucracy. Aim to eliminate the most performative and pointless government swamp jobs—about 30% of total—in the next three to five years. In addition, review the purpose and performance of government-subsidized jobs every fifth year. Cut or reform programs that are no longer worth funding.

Less of the Same

Policies that stimulated economic growth in the second half of the 1900s now impede it. More of the same will get us more of the status quo—economic underperformance coupled with political dysfunction.

We cannot depend on the swamps to reform themselves. The fossil fuel lobbyists can’t envision a world with cleaner, cheaper energy. Political swamps do not entertain any future different from the present, with its jobs and departments that have outlived their usefulness or have become too expensive for taxpayers.

Every country needs some stimulus and buffers. However, we cannot fund the things that matter today and tomorrow unless we decline to fund the swamps. It’s time to let go of policies designed for last century and face the challenges of today. It is time to develop new systems that will create prosperity well into the 2050s.